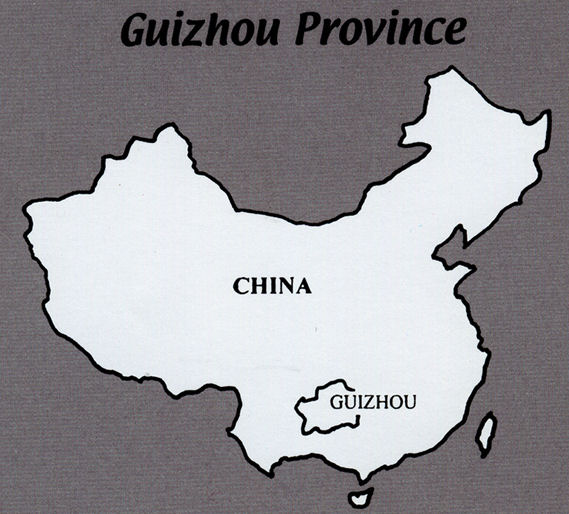

Guizhou is a mountainous

province and one of China’s most diverse, with over 14,000,000 people designated

as ethnic minorities. Due to the mountainous geography and ethnic diversity,

cultural traditions have remained strong and many minority women still make

their festival garments and baby carriers in traditional ways. Each minority

group has distinctive dress that identifies them with their group and even

their village. Still today, women spend long hours making their festival costumes

and baby carriers.

Symbolism Baby carriers are one of the first items a new bride might embroider. Great time and love goes into making baby carriers and hats that act as talismans to protect the child and ward off evil. Embroidered symbols express promises for good health and fortune, while bells and pom-pons ward off evil. Each minority group favors particular symbols that tell their stories. Some symbols, such as the butterfly, are used by many groups, but retain separate meaning. The Butterfly Mother is important in the creation mythology of the Hmong (Miao), so the butterfly symbols used on their baby carriers hold specific importance as well as expressing good fortune and health. The legend tells that the gods created the earth and planted many maple trees. A butterfly flew from one maple tree and laid 12 eggs. One of the eggs hatched and gave birth to Jian-ian, who gave humans the ability to procreate. The butterfly is therefore the creator of all living beings and brings children good luck and good health, while granting women the power of fertility. For the Hmong (Miao) in particular, dragon symbols are very important. Dragons come from one of the eggs of Mother Butterfly and live among the people. Dragons are associated with rain, affecting the growing of rice and other important crops. Hmong (Miao) dragons come in many forms, with greater power given to animals that have changed into dragons. Other dominant symbols are birds, flowers, fish, and coins. |